Writing Trauma, History, Story: The Class{room) as

advertisement

Writing Trauma, History, Story:

The Class{room) as Borderland

DAPHNE READ

The focus of most nations' collective myths is on their struggle against oppression

and on the sacrifices made by their martyrs. Do nations, in order to function

effectively, needasharedhistory oftraumatoforge asense of national community

that creates a sense of belonging and security in its citizens?

Alexander C. McFarlane and Bessel A. van der Kolk

The function of social denial of the past needs to be better understood.... Can

individuals and nations afford to face the awful truths about their past, as long as

life's basic necessities have not been provided for?

Alexander C. McFarlane and Bessel A. van der Kolk

Everybody knew what she was called, but nobody anywhere knew her natne.

Disrememberedandunaccountedfor, she cannot be lost because no one is looking

forher,andeveniftheywere,howcantheycallheriftheydon'tknowhernatne? ...

It was notastory topass on.. ..

It was notastory to pass on.. ..

Tbisisnotastorytopasson.. ..

lkkwa:l

ToniMorrison

Writing: The Local

This, too, is not astoryto pass on: In Edmonton, Alberta, onNovember28, 1993,Joyce

Cardinal was doused with gasoline and set on fire by an unknown assailant. She died

on December 21, 1993, in the University of AlbertaHospital. This story haunted a

student who was an emergency nurse ondutywhenJoyce Cardinal was brought to

the hospital. Through several courses over two years this studenttriedto put the story

into words; she wanted to give voice to the woman, to express solidarity with other

victims of violence, to express the anguish and horror, and to find a way through it

to ... what? It was a story that could not be told.

How does one make sense of this story?

ThinkingofPatriciaWilliams'studyofthedisappearanceofTawanaBrawleyinto

media representations of the silenced woman, one could retrace the scant narrative

details available in the local newspaper and note the terrible symbolism as burning

trash at midnight took the shape ofa woman, and later, aNativewoman, who had a

severe speech impediment and left asmall partyto walk home alone. Thinking ofAlice

l06]AC

Walker's tribute to the spirits of the emptied, abused "Saints" and to the everyday

creativity of"our mothers' gardens," one couldhonourandmournthecreative spirit

evoked in the family's vigilforthe beloved:

Joyce Cardinal's family clings to acrochetedafghan, awom piece of wool which bears her spirit

while she lies swathed in bandages in ahospital bed Only those closest to her could understand

her garbled speech, but Cardinal could knit and crochet in an even hand. The oddities only

endeared the 36-year-old to herextendedfamily, who usedtoworry about Cardinal's trusting

nature but never imagined the violence she would become a victim of.' (plischke)

Thinking tangentially of Gayatri Spivak's reflections on sati and the question of

readingtheagencyofsubalternwomen,oneknowsthattheviolenceandhorrorof

] oyce Cardinal's death will never be recuperated by the discovery of aletterto the

future. And thinking of a poster put out by the Women's Bureau ofthe Canadian

Labour Congress to commemorate both the fourteen women engineering students

at the EcolePolytechnique in Montreal who were killed on December 6, 1989, and

the 97womenwho were killed in domestic violence in 1988 in Canada, one remembers

an epitaph, arallyingcry:"Firstmoum Then workforchange."

I begin with the death of]oyce Cardinal for many reasons. It was passed on to

mebyTanyaCahoon, the emergency nurse, who, during the weeks before Cardinal's

death, spoke very little about the story for legal, ethical, and human reasons. Later,

as she tried to write the experience, she abstracted the pain as too much forherreaders,

too much to bear, finally reaching an impasse in the boundary between the particular

and the universal. At one level, her writing, as I have constructed it, and my writing

of this "story" exemplify well-rehearsed political and ethical issues of representation

in feminist and post-colonial encounters between the intellectual and the Native

(Chow, Royster, Spivak, Trinh). But TanyaCahoon's work-her struggles-as nurse,

student, writer complicates any tendency to theoretical or polemical reductivenessin

postcolonial critiques of representation. Less obviously, herworkchallenges the

teacher-student hierarchy which underlies much discussion of composition theory

and pedagogy, and affirms the student, not as "precocious child" {regardless of age) ,

but as apprentice-intellectual. The focus on trauma, memory andwriting inthis story

suggests a way of rethinking questions about experience and writing in the academy

and of revisioningthedivide between students' writing and "legitimate" literary texts.

But inorderto elaborate these arguments, I need first to theorize the site ofteaching

and learning. From my location at aCanadian university in arelativelysmall, deeply

conservative, oil-rich, western province, I suggest that the current paradigm of the

classroom as multicultural contact zone applies best in those circumstances where

there is substantial critical mass, but that in locations where the hegemonic mass far

outnumbers the oppositional groups, the paradigm of borderland-broadly conceived-is more productive for critical teaching and learning. 1

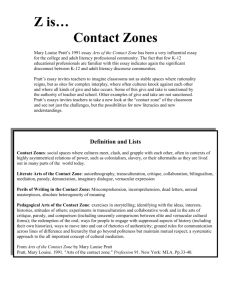

The Class(room): Community, Contact Zone, Borderland

Postcolonial theory offers a number of possibilities for conceptualizing the space of

the teaching encounter, the space I clumsily call "the class (room) ." While the class

The Class(room) as Borderland 107

is much more than whattakes place in the time and space ofthe course, the play on

class and classroom suggests that the physical classroom helps to "invent" the class as

community. The class (room) can be theorized as an "invented" or "imagined

community" (Anderson, Pratt), with the attendant strengths and limitations of

"community"; or the class (room) may be seen as a "contact zone" (pratt, Ellsworth2),

mirroring the social conflicts ofamulticultural society; or the class(room) may be seen

as a "borderland" (Anzaldua, Allen).

The concept ofthe class as invented community is potent for precisely the reasons

RaymondWilliamsidentifiesinKeywords:

Community can be the warmly persuasivewordto describe an existing set of relationships,orthe

wannly persuasive wordto describe an alternative set of relationships. What is most important,

perhaps, isthat unlike all otherterms of social organization ~tate, nation, society, etc.) it seems

neverto be used unfavourably, andneverto be given any positive opposing or distinguishing

tenn. (66)

However, the concept ofcommunity has come under attack as anidealist,homogeniz·

ing construct in the se,rvice of the nation (pratt, "Linguistic Utopias"). Benedict

Anderson's brief description of the nation as "imagined community" reiterates

Williams' point: "[the nation] is imagined as acommunity, because, regardless of the

actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each, the nation is always

conceived as adeep, horizontal comradeship. " But the irony, he immediately notes,

is that "it is this fraternity that makes it possible, overthepasttwo centuries, forso many

millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly to die forsuch limited imaginings"

(1). Continuing in this vein, Edward Said, speaking of interpretive communities,

distinguishes between the (negative) religious community and the (positive) secular

community. Whereas areligiouscommunity "is basedprincipallyon keepingpeopleout

and on defending atiny fiefdom ... on the basis ofamysteriouslypure subject's inviolable

integrity," asecularcommunity"requires amoreopensenseofcommunity as something

to be won and of audiences as human beings to be addressed" The ideal interpretive

community for Said is secular, noncommercial and noncoercive ("Opponents" 25). In

the secular class(room), imagined as community, we might invoke the concepts of

democracy, equality, dialogue,andvoice, urgingeveryoneto participate openly and fully

in a rational conversation. In such an ideal space the classroom might become a "safe

place." However, safety in the realmofthe rational is acomplicatedissue, as Patricia

Montur~Kanee,lawprofessor,mother,andcitizenoftheMohawkNation, writes:

The overwhelming sense I hadofmy first fewyears of university education was ofhavingfinally

found a place where I belonged. This is not so much a reflection of the university I attended

but of where I was in my personal development. I can always remember being a"thinker." My

friends have always told me I am very logical. I was well suited to the requirements of a

university life. It was not until years laterthat I understood that this sense of belonging was

a false one. My sense of belonging grew out of my status as a survivor of various incidents of

abuse. In university, I did not have to feel, just think. Feelings were what I was trying to avoid

Years later I came to understand that the sense of belonging I felt was really the comfort I took

in finding an environment where feelings were not essential. (11)

108]AC

There are dangers inassumingacommunity-in the class(room)-basedon the

utopian concepts ofequality, fraternity, and liberty (pratt, Ellsworth). In the context

of contemporary multicultural national realities (tn the United States specifically),

Mary Louise Pratt suggests that the class(room) should more properly be defined as

a "contact zone." Pratt defines contact zones as "social spaces where cultures meet,

clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations

of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out in many

parts of the world today" ("Arts" 34). In contrast to Anderson's "imagined

community," the contact zone foregrounds the social heterogeneity and conflict that

are typically subsumed in theideaofthenation ("Arts" 37-38). In the contact zone

of the class (room) , then, students and teachers negotiate knowledges, conflicts and

debates born out of real social differences and interests, and the classroom is not

"safe." However, the contact zone also includes a restricted sense ofcommunity in

the identified need among different groups for "safe houses." Pratt defines these in

Anderson's terms as: "social and intellectual spaces where groups can constitute

themselves as horizontal, homogeneous, sovereign communities with high degrees of

trust, shared understandings, temporary protection from legacies ofoppression" (40).

Given Pratt's critique of "community" as a functionalist, idealist concept ("Linguistic

Utopias"), it is ironic and telling that the "imagined community" persists in her

formulation of the contact zone, displaced from the hegemonic centre to the

oppositional margins. It is important to query the metaphor of "safe house" and its

assumptions of "high degrees of trust, shared understandings, [and] temporary

protection." What guarantees these conditions inthe "safe houses" of the class (room),

anymore than in the nation? As apolitical and legal metaphor, "safe house" does indeed

evoke a place of refuge and protection from violence and oppression, but from other

points ofview, for example victims ofdomestic abuse andothertraumas, no place is safe.

This question of safety points to aconceptual limit to the contact zone as away of

responding to the contemporary theoretical emphasis on difference, struggle, conflict,

and oppression in teaching. As Pratt has theorized the contact zone, the social space of

teaching is both contact zone andimaginedcommunity, but theway in which theterms

have been defined situates the argument squarely within national debates about

multiculturalism and educational reform. What is at stake in theorizingtheclassroom

as contact zone is clearly articulated in Pratt's essay "Daring to Dream: Re-Visioning

Culture and Citizenship," which elaborates apolitical commitment to multiculturalism,

to "anew nationaisubject-afigureRenatoRosaido hascalledthepol)glotcitizen," (6) and

to the "decolonization ofculture and the national imagination" (14), also described as

"thedecolonizationofconsciousness" (15). Theclass{room) as contact zone is, in effect, a

microcosmofthemulticulturalnation,andthe"safehouse"isthemetaphorical~promising

each marginalized group its entitlement to citizenship and proprietorship. Pratt writes:

Formany people it has become imperative to be able to live out particular identities and group

historiesaspan ojone'scitizenship, ratherthan as an obstacle to citizenship-imperative to feel

not just that one is entitled or allowed to be here, butthat one belongs here, that one is entitled

to proprietorship ofthe nation'sinstitutions asfuUy as people ofthetraditionally dominant or

normative group. ("Daring" 4)

The Class(room) as Borderland 109

As an intervention in public debates about citizenship, culture and consciousness, the

contact-zonemodelofteachingprivilegesthepublicsphere,andthisiswhere I locate

the limits of the model. It implicitly sustains the boundaries between the public and

the private. As I have suggested in the problem of "safe houses," the model does notcannot?-adequately deal with such issues as domestic abuse and trauma.

One might go further and suggest that this privileging of the public over the

private sustains the maintenance and privileging of other hegemonic, middle-class

values in composition: propriety and cleanness over impropriety and dirt, decorum

and politeness over anger and aggression, etc (Bloom). In discussions of"faultlines"

(Miller) in the contact zone in composition teaching, two other related boundaries

emerge: that between teachers as authoritative readers and students as incompetent

writers, and that between "literary" texts and students' writing. Interestingly, these

hierarchies replicate those identified by Pratt in her critique of the games-model in

linguistic research on discourse communities. "In these games-models, " she writes,

"only legitimate moves are named in the system, where 'legitimate' is defmedfrom the

point of view of the party in authority" ("Linguistic Utopias" 51). As one example,

she cites research on "teacher-pupil language, " which "tends to be described almost

entirely from the teachers' point of view" (51).

Students are present, in other words, only as they are interpellated directly by teachers, and

even then in a reduced and idealised fashion. Parodies, refusals, rebellions and so fonh fall

outsidethe account, and with them the struggles over disciplining that are such afundamental

pan of the schooling process. (52)

RichardMiller's analysis of the controversy surrounding the student essay "Queers,

Bums, and Magic" is fascinating; he takes up Pratt's question, "What is the place of

unsolicited oppositional discourse, parody, resistance, critique in the imagined

classroom community?" ("Arts" 39; qtd. in Miller 390), and reshapes it to ask, how

do teachers in the contact zone respond when this oppositional discourse is racist,

sexist, and!or homophobic (391)? His reframingand investigation of this question

highlight some of the unquestioned, left-liberal assumptions about teaching in the

contact zone. First, there is a general consensus on the difference between "good"

and "bad" oppositional stances, and for many, it is the teacher's (middle-class) duty

and right-even burden-to punish the "wrong" stance, either by invoking the law

Oiterally) or by penalizing the grade. A second common assumption-orpresumption-isthat the teacher as competent and authoritative reader "knows"whatthe

student has written; that is, student writing is essentially transparent. This belief, it

seems to me, underlies both the teacher's non-recognition, or refusal, of the

"unsolicited oppositional discourse" ("Arts" 38-39) in Pratt's example of herson's

grade four writing assignment, and the popular, punitive response to the professor's

second-order summary of the anonymous studentessay"Queers, Bums, and Magic"

in Miller's example (392-93). In spite of a commitment to the space of teaching as

contact zone, it seems, teachers refuse student writing the status of the "legitimate"

arts of the contact zone and continue to discipline student writing on the basis of the

traditional middle-class values embedded, as Lynn Bloom so convincingly argues, in

the ideology of freshman composition.

110]AC

In this connection, both Miller and Pratt refer to student writing and

autoethnographicwritingas examples of "the literate arts ofthe contact zone" (pratt,

"Arts" 37), and both, interestingly, enact a separation between the two "genres. "

Miller shifts from the specific problem posed by one student's essay to his own

pedagogy in the contact zone: "I have tried to develop a pedagogical practice that

allows the classroom to function as a contact zone where the central activity is

investigating the range ofliterate practices available to those within asymmetrical

power relationships" (399). Miller's course approaches writing through reading:

By having my students interrogate literate practices inside and outside the classroom, by having

them work with challenging essays that speak about issues of difference from a range of

perspectives, and by having them pursue this work in the ways I've outlinedhere, I have been

trying to create acoursethat allows the students to use their writingto investigate the cultural

conflicts that serve to define and limit their lived experience. (407)

Miller demonstrates his approach through a discussion of a student's approach to a

chapter from Borderlands/LaFrontera, by GloriaAnzaldua Having begun with the

problem of "unsolicited oppositional discourse" in students' writing, he tackles the

issues of student consciousness and the decolonization of the national imagination

by structuring his reading and writing assignments around published texts like

AnzaldUa's autoethnographicessay. Through this course, students become more selfreflexive, critical readers of texts in the world and of the text oftheir own experience,

but unliketheauthorof"Queers, Bums, and Magic," they are not asked to generate

their own autoethnographictexts.

Pratt's distinction between student and published witing is a little different.

TowardstheendofherrecuperativediscussionofGuamanPoma'sautoethnographic1he

FirstNewOmmickandGoodGovernment,Prattwrites:

Autoethnography, transculturation, critique, collaboration, bilingualism, mediation, parody,

denunciation, imaginary dialogue, vemacularexpression-these are some of the literate arts

ofthe contact zone. Miscomprehension, incomprehension, dead letters, unread masterpieces,

absolute heterogeneity of meaning-these are some ofthe perils of writing in the contact zone.

("Arts· 37)

What interests me is that the student example Pratt cites, herson's writing, is,asMiller

notes, "oddly benign" (390) in the context of her discussion of the "perils of writing

in the contact zone." To return to the discussion ofsafety, it is also" oddly safe, " in

that the child's writing is recuperatedfrom theteacher's incomprehension by alinguist

mother and publicly presented as an instructive and entertaining anecdote at a

conference on literacy. This example, in lieu ofanexample from "a contemporary

creation of the contact zone" (35), succeeds in keeping the "rage, incomprehension,

and pain" of teaching in the contact zone at bay and reinforces the utopian goals of

the contact zone.

Pratt's"Arts of the Contact Zone" and "Daring to Dream: Re-visioning Culture

and Citizenship" both had their origins as keynote addresses to professional

conferences, and both conclude with avision of future possibility and strategies for

The Class(room) as Borderland 111

change-an important rhetorical structure in political activist analysis. These

gestures to the future, the commitment to amore inclusive, just society, are absolutely

vital in imagining and creating community. What I am suggesting, however, is that

the focus on the positive in the discussion of the contact zone may also be linked to

a more pervasive institutional ambivalence about the categories of experience, the

personal, and trauma. In mainstream university teaching, there is a deep reluctance

to deal with, for example, trauma as students experience it. Trauma "belongs" in the

texts we study, not in the texts students write. In teaching in the contact zone, Pratt

suggests that some kinds of experience belong in the space of safe houses: "Where

there are legacies of subordination, groups need places for healing and mutual

recognition, safe houses in which to construct shared understandings, knowledges,

claims on the world that they can then bring into the contact zone" ("Arts" 40). But

to revisit the question ofsafehouses again, what happens in theclass(room) when there

are simply representative individuals, not groups, who have experienced oppression?

Ifthere is no critical mass to support the student, no group with a shared legacy of

subordination, how do the single Native or Metis student or the two Asian students

in the class participate in the contact zone? And what about the student who, on the

surface, experiences mainstream privilege, but has also suffered severe sexual abuse,

or is gay and mayor may not be "out" in a legislatively anti-gay province?

The contact zone has been articulated in relation to struggles to achieve a fully

democratic multicultural nation in the United States, and may be most relevant in

contexts where different cultural groups are supported by strong, politicized, selfidentified communities. In my teaching context, however, it may be more appropriate

to theorize the class (room) as borderland, where borderland is understood in the

multiple senses of Gloria Anzaldua's BorderlandslLaFrontera. The borderlands,

Anzaldua writes, can be physical, psychological, sexual, spiritual: "In fact, the

Borderlandsarephysicallypresentwherevertwoormoreculturesedgeeachother,

where people ofdifferent races occupy the same territory, whereunder, lower, middle

and upper classes touch, where the space between two individuals shrinks with

intimacy." In terms that echo Pratt's description ofthe contact zone, Anzaldua writes:

It's not a comfortable territory to live in, this place of contradictions. Hatred, anger and

exploitation are the prominent features of this landscape. However, there have been compensations forthis mestiza, andcertain joys.Living on borders and in margins, keeping intact one's

shifting and multiple identity and integrity, is liketryingto swim in anewelement,an "alien"

element. There is an exhilaration in beingaparticipant in the further evolution of human kind,

in being "worked" on. (preface np)

Anzaldua's concept of the borderlands clearly intersects with the contact zone,

but in its inclusion of psychological, sexual and spiritual borderlands, it is not tied to

a specific national, multicultural agenda. I link it, instead, to what Edward Said

describes as the radical imperatives of secular criticism:

[C]riticism must think of itself as life-enhancing and constitutively opposedto every form of

tyranny, domination, and abuse; its social goals are noncoercive knowledge produced in the

interests of human freedom. ("Introduction" 29)

112JAC

Said is writing about the work of professional intellectuals, about the production of

knowledge, but I think that his statement can be rewritten-provocative1y-to

describe the imperatives of teaching. Thus: "teaching must think ofitse1fas a lifeenhancingactivity,constitutivelyopposedto every fonn oftyranny, domination, and

abuse; its social goals are noncoercive knowledge produced in the interests of human

freedom."

The radical imperatives of teaching in the borderland include facing trauma, one

of the developing areas of research in cultural and literary studies. Alexander

Mcfarlane and Bessel van derKolk, major figures in the fieldofpsychiatricresearch

ontrauma,notethatartists"presenttheissuesoftraumawithaclaritythat contrasts

sharply with the traditional obfuscation of these issues in the field of mental health"

(45). And indeed, much of the writing in the borderlands is an exploration oftrauma.

Texts like Anzaldua's BorderlandslLaFrontera, Toni Morrison's Beloved, a novel

exploring the psychic traumas ofslavery, andElly Danica's incest narrative, Don 't:A

Woman-sWord,plungethereaderintotheterritoryoftrauma,memory,andsocial

responsibility. McFarlane and van der Kolk note that, in addition to creative

transfonnation (or sublimation), trauma may motivate individuals toworkforsocial

change (33), and they dedicate the edited collection Traumatic Stress: The Effectso/

OverwhelmingExperienceonMind,Body,andSocietyto"NelsonMandelaandallthose

who, after having been hurt, work on transfonningthe trauma ofothers, ratherthan

seekingoblivion or revenge." Speaking ofthe Truth andReconciliation Commission

initiated by Mandela, van der Kolk writes:

In articulating the vision of how his people should overcome their legacy oftrauma, Mandela

has put into action aprogratn that is based on ahope for understanding, instead of vengeance;

for reparation, ratherthan retaliation; for ubuntu, not victimization. Bdievingthat only aTrue

Memory Society can guarantee dignity, peace, andstability, Mandela ... proposes that before

perpetrators can be forgiven, there first needs to be an honest accounting and a restoration of

honor and dignity to victims; the facts need to be fully acknowledged in order to heal the

wounds ofthe past. (xxi)

In dealing with trauma on a national scale, Mandela's commission illustrates

Judith Hennan's point that the public recognition and study oftrauma depend on the

legitimizing support of political movements "powerful enough ... to counteract the

ordinary social process ofsilencing and denial. "

To hold traumatic reality in consciousness requires asocial context that affums and protects the

victim and that joins victim and witness in acommon alliance. For the individual victim, this

social context is created by relationships with friends, lovers, andfatnily. Forthe larger society,

the social context is created by political movements that give voice to the disempowered. (9)

In the absence of such political movements, Herman continues, "the active process

of bearing witness inevitably gives waytothe active process offorgetting" (9).

What makes it possible to theorize the class (room) as an inclusive borderlandis

the political and theoretical alliance between postcolonial and feminist movements.

However, to argue that teaching in the class(room) as borderland carries the social

The Class(room) as Borderland 113

responsibility of bearing witness to traumas of different kinds is not an easy position.

In the first place, teachers are not generally trained psychologists: though education

may be therapeutic, it is not professional therapy. Secondly, trauma challenges the

traditionalseparationbetweentheacademicrealmoftheintellectualandtheprivaterealm

ofexperience. Traumaisdeeplydisturbinganddeeplychallenging,asHermanwrites:

To study psychological traumais to come face to face both with human vulnerability in the

natural world and with the capacity for evil in human nature. To study psychological trauma

means bearing witness to horrible events. When the events are natural disasters or "acts of

God,' those who bear witness sympathize readily with the victim. But when the traumatic

events are of human design, those who bear witness are caught in the conflict between the

victim and the perpetrator. It is morally impossible to remain neutral in this conflict. The

bystander is forced to take sides. (7; also qtd. in McFarlane and van der Kolk 28-29)

As teachers and students in the class{room), we too come face to face with human

vulnerability, sometimes with traumas-personal, cultural, historical-and sometimes with the human capacity for evil. It is somewhat easier (though this is arelative

term} to discuss trauma in published texts than to respond to trauma in the social space

of teaching. We are caught between "the universal [?] desire to see, hear and speak

no evil" and the responsibility of "bearing witness" (Herman 7). But ifwe choose not

to respond, then by default we too participate in social repression.

This view of teaching in the borderland emphasizes the critical importance of

communal sharing and witnessing. A haunting scene towards the endofBelovedspeaks

to the possibilities of this kind of work in the class (room) :

Paul Dsitsdown in the rocking chair andexaminesthe quilt patched in camivalcolors. Hishands

are limp between his knees. There aretoo many things to feel about this woman. Hisheadhurts.

Suddenly heremembers Sixotryingtodescribe what he feltaboutthe Thirty-Mile Woman. "She

isa/riendofmymindShegatherme,man. 1bepieceslam,shegatherthem.andgivethem.backtomeinall

therigbt order. It's good, you know, when you gotawoman who isafriendofyourmind

Heisstaringatthequilt but he isthinkingabout her wrought-iron back;thedelicious mouth

still puffy at the corner from Ella's fist. The mean black eyes. The wet dress steaming before the

fire. Hertendemessabout his neck jewelry ....How she nevermentionedor looked at it, so he did

not have to feel the shame of being collared like abeast. Only this womanSethe couldhave left

him his manhood like that. He wants to putbisstorynext tobers. (emphasis added; 272-73).

Although Sixo and Paul Dare describing intimate relationships in the context of

shared oppression, their experiences can be extrapolated to the class (room) . Sometimes, in the borderlandsofteaching, we {the collective class) become "friends of your

mind, " gathering the pieces and giving them back "in all the right order." And when

this happens, it is often because we put our stories next to each other, affirming our

humanity and producing "noncoercive knowledge ... in the interests of human

freedom" (Said, "Introduction" 29). This witnessing takes place when astudentwrites

and then reads to the class an essay on the suicide of an intimate friend, or an essay

on being the girlfriend of a man charged with rape, or an essay on sexual abuse, an

essay on a friend's self-mutilation, on being physically different, on religious

fundamentalism, homophobia and coming out-in short, when students write on

beingwomen and men in today'sworld.

114JAC

In order forthis process to occur in the class (room) , we need to reconsiderthe

boundaries between students and teachers and between student texts and literary texts.

What happens, for example, if we apply post-colonial and feminist critiques of

encounters between the intellectual and the Other to the relationship between teacher

and students? or if we apply poststructuralist concepts of the subject and the text to

student writing? I argue that students, like teachers, are intellectuals-apprenticeintellectuals, researchers and writers-who come from diverse social groups. Hence

the encounter between and among teachers and students is an encounter among

intellectuals who are differently constituted as subjects. This framing of the teacherstudent relationship is not intended to erase the real institutional inequality or

differences in knowledge between teachers and students, but it has certain consequencesforclass(room) practice. One of the most important is that it shifts the focus

from a dyadic, hierarchical teacher-student relationship to acollective relationship,

where students become agents, subjects in the process of producing knowledge.

Writing: The Borderland

One of the tasks in the class (room) is to articulate knowledge of the borderlands

through reading, talking and writing. Paula Gunn Allen argues that:

The process ofliving on the border, of crossing and recrossing boundaries of consciousness,

is most clearly delineated in work by writers who are citizens of more than one community,

whose experiences and languages require that they live within worlds that are as markedly

different from one another as Chinatown, Los Angeles, and Malibu. (33)

In the university class (room) weare all writers (hence intellectuals). Though we may

not live in markedly different worlds, I hypothesize that we all live "on the border"

(however defined) and that we all live with uncomfortable contradictions. The most

visible borders are those that are publicly constituted, but as Anzalduasuggests, there

are also private, intimate, internal borderlands which we negotiate daily and which we

alsobringtoourintellectualwork. Wecannotpresume,however,thatweareallcitizens

ofmorethan one community: we are not all enfranchised within the communities we

inhabit. Thus one of the challenges in the class(room) is to find ways of making

different knowledges public and to produce different knowledges in the process.

To a certain extent, articulating the borderlands is a complex process of

communal storytelling which moves through texts, theory, and personal experience.

"Storytelling" in this sense invokes research and critical skills as well as literary craft:

it is "theorizing in narrative form" {Royster35),autoethnography, autobiography,

memoir, critique. ("The best essays,"Wendy Lesserobserves inHidinginPlainSight,

"are those which exist on the borderline between criticism and autobiography" [ixJ.)

In collective storytelling in the class(room), the borderlands move from the "outside"-the fictional, the textual, the abstract "outthere"-to the "inside"-the local

and particular. Ifthe process works, if asecular interpretive community develops in

the class (room) , then akindofcommunal magic can spark extraordinary intellectual

activity, as when students begin to build on and respond to each other's work. (For

example, in one class, essays by several youngwomenon growing up female sparked

several young men to write about growing up male.)

The Class(room) as Borderland 115

Few undergraduate students would immediately identify themselves as "writerintellectuals," engaged in the process ofcollective storytelling and the production of

newknowledges.Oneofthechallengesintheclass(room)istofindwaystoencourage

this recognition. In acourse on introductory nonfiction writing (which hadits origins

in conventional models of essay-writing, but which 1teach as creative or literary

nonfiction), I use a workshoppingprocess where the students work on two drafts of

their essays in small groups, present the final version to their groups, and then

designate one person from each group to read her orhis essay to thewholeclass. This

process shifts the emphasis away from the standard evaluation-orientedessay, written

only for the teacher, to an awareness of multiple audiences. Students also explore the

differences between public and private writing, and become aware of a variety of

ethical considerations in telling nonfiction stories that involve people other than

themselves. Finally, students (may) learn to take risks in "exposing" what matters to

them in profound ways. Students often see risk-taking as a willingness to expose the

personal-and usually the first examples they encounter are indeed revelations of

personal experience. But more fundamentally, risk-taking isthewillingness to explore

and to commit to paperwhat one really thinks-to write to discover what one doesn't

know one knows. Taking risks, 1urge, is fundamental to good writing, but the

willingness to take risks depends on three levels of trust: trust in the teacher, trust in

each other, andmost importantly, trust inthemselves. Trust in all three cases is earned

in the final analysis, not a given, but trust can also be a promise to the future ("1 will

take a chance and trust the process for the moment"). In a full-year writing course,

students experience the often astonishing growth oftheir peers and themselves as this

process of trust and risk-taking develops. Overtimetheycometoserveaswitnesses

to each other's stories, where the private becomes public (stories ofgrowing up, abuse

and violence, etc). And they begin to write as an active, self-challenging, self-affirming

community.

But storytelling is risky in the academic setting: the combination of narrative and

personal experience is subject to whatJacquelineJones Royster calls "the power and

function of deep disbelief" (34). That is, if the audience refuses to perceive-and

legitimate-narrative as aform of theorizing, then the writer is reduced to the status

of entertainer: "a storyteller, a performer" (35). Royster is referring specifically to

African American writing, but the argument holds true for students and teachers in

the borderland There is adeep-seated academic resistance to the personal, aresistance

defined for me recently inaclass discussion of "taboos" in academic writing: astudent

voice from the boisterous throng comically opined, "lis aprofanity!" Laterin the year,

another student, struggling with issues of voice, authenticity, and difference in

academic writing, observed painfully, "ihas no body." At the end oftheyear, astudent

writing about andto the class commented on the "coming out" process so manyhad

experienced-and the class had witnessed-as they found ways of claiming voice in

their writing. Sometimes the witnessing takes unexpected forms, as when a male

studentvolunteeredtoreadanessaytotheclassforafel1owclassmate, who didn't think

she could make it through her essay-on sexual abuse and love-without breaking

down.

116JAC

Student "storytelling" demands the craft of skilled writers, but it also demands

the acuity of skilled listeners and readers. When the class works as an active,

challenging community, students read each other's work with the same respectful

attentiveness as published texts, and conversely, subject published work to the same

kind of scrutiny and questioning as their own work. They learn not only how to

"show," but how to read what is shown in acritical way. For example, whenastudent

read an essay on a self-mutilating friend in high school to the class, the discussion

focused instantly on what the essay (unintentionally) showed, but did not tell: the

failure of the adults and the institutions in the girl's life who knew about her traumatic

history and did nothing to respond to her pain.

One of the challenges in the class (room), I have argued, is to find ways of making

different knowledges public and to produce different knowledgesin the process. And

one of the ways in which this happens is through the exploration of trauma. In the

borderlands, trauma cuts across the categories of, and the communities rooted in, race,

class, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, etc. I suspect, however, that the

traumas and oppositional social struggles which come to light in theclass(room) tend

to be those which are either already legitimized in the public and academic spheres

or forcefully articulated by strong social movements. Hence, many of my examples

of student writing refer to sexual abuse and sexual orientation, issues articulated

primarily by students situated within the white settler "mainstream" in Alberta. For

the students who fall into the categories of"aboriginals" and "visible minorities"

(official federal government designations used in the university), where the communities are small and lacking in power, the struggles against racism are often coded in

narratives of self-improvement and individual triumph, as is "appropriate" within a

hegemonic provincial conservative ideology. Such students,however, may resist the

pedagogical pressure to participate in acommunityofwriters and readers, and choose

instead to write for the teacher's eyes only. This resistance points to the limitations

of the model of class (room) as (benevolent) borderland (one student wrote, for

example, in an essay for my eyes only, that the university occupies Native land).

Resistance of this type is analogous to the resistance Doris Sommer discerns in

RigobertaMenchu's refusal to divulge secrets to the anthropologist Elisabeth BurgosDebray. The teacher, ifvisiblya white middle-class representativeofthe institution,

may not be an ideal reader, mayinfact be an "incompetent reader," andherpedagogical

desire to explore and "know" trauma mayenact furtherviolation (Sommer417). From

this perspective, it might be argued that the class (room) as borderland, as I've

conceptualized it, is simply another space promoting liberal individualism; that is, in

focusing on the ways in which trauma cuts across social categories, the class(room)

as borderland privileges individuals and personal experience and assumes that the

class can function as ahomogeneous "imagined community. " The resistance of some

students to writing for the class as audience can be seen as a political setting of

boundaries; respect forthese boundaries, as Sommer writes, "demands hearing silence

and refusal without straining to get beyond them" (416).

However, the process ofexploringand witnessingtraumacan serve to counteract

theharsh individualism offundamentalist conservative ideology enacted, for example,

The Class(room) as Borderland 117

in punitive provincial social policies, where the "victim" is always to blame. For some

borderland intellectuals-for some students-the process of coming to knowledge

through reading and writing can be as life-saving as Anzaldua's: "Books saved my

sanity, knowledge opened the locked places in me and taught me first howto survive

and then how to soar" (Preface). Sharon Jean Hamilton echoes Anzaldua in her

literacy narrativeMy Name's not Susie. Now a professor of English at an American

university and long "immersed in literacy development" (xiv),Hamiltonputs her story

next to those of her students. Hamilton was born in 1944 in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and

"apprehended" by the Children's Aid Society before she was one (12). By the time

she was adopted at the age of three and a half, she had changed foster homes eighteen

times, had endured various kinds of abuse, and had been "branded a borderline

autistic, a potential sociopath, [and] a bad apple unlikely ever to finish school or hold

a job" (4). "Literacy," she writes, "saved my life" (xiii). When she was eight, "in order

tosilencemyconstanttalkingforafewminutes,"hermotherencouragedhertowrite

down her memories of her life before adoption. This encouragement, so insightful

at one level, was also ideologically restrictive. "Whenever reliving these early horrors

upset me," Hamilton writes, "my mother pointed out that the troubles I was writing

about paled in comparison to the troubles of people I was reading about. I may have

been unwanted, malnourished, and beaten, but I didn't starve or freeze to death like

the little match girl" (my emphasis, xiii). Hamilton comments that, "It was awhole

new lesson for meto learn much later that the dramas of our lives can be as soul-searing

and soul-shaping as the great dramas ofliterature" (xiii). It would be easy to read

Hamilton's literacy narrative as aconfirmationofindividualist struggle andthe power

of education, but it speaks more directly to the kind of work we can do in the

class(room) in locating traumatic experience-and the writing of it-in its larger

cultural context and social history.

In "Red Running Shoes," an incest narrative, which is also a literacy narrative,

Jean Noble asks, "what does it mean to me as a white, working class lesbian to be a

survivor of childhood sexual abuse?" (28). Noble, who grew up inKingston, Ontario,

writes that books saved her life too, though in a different way from Hamilton and

Anzaldua. Her hiding place-the place to which her mind fled during the sexual

abuse-was the OxfordEnglishDictionary, as constructed by her parents:

it was one ofthose deals from agrocery store where you buy each part once a month and when

you have all the pieces you send them away andaleatherbound version of this huge dictionary

is returned to you. it is about seven inches thick and it was the heaviest and biggest book i had

ever seen when i was a kid. nobody ever used it but i loved to stroll through it .... this was

where i hid.... nobody would have ever looked for me there and it has kept me safe. (42)

"RedRunningShoes" is a story in process, much like the texts of students writing

through their experiences oftrauma. Its ending is abeginning, a birthingofthewriter:

"call me dykewomyn lesbian whore butch witch call me athene medusa fori have come

from myself" (42). The writer has become "speaker and audience, participant and

witness, author and subject" (29).

118JAC

ForMariaCampbell, aMetiscommunityworkerwhonow livesinSaskatchewan,

writing her life was part of her struggle to keep off the street after she was fired from

her job with aNative organization in the early 1970s. In an interview, she explains

how she came to write her autobiography Halfbreed:

I hada friend who was aQuakerlady. She lived in Edmonton. Hername was Peggy. She was

a much older lady and we were very close. She was one of the people who really helped me

to find books to read. She told me, at one time, "If things get so bad, and you've got nobody

to talk to, write yourself a letter." (o'You Have to Own Yourself'" 45)

Campbell started that letter to herself, and two thousand pages later, it arrived in the

hands ofJack McClelland, whopublishedHaljbreedin 1973 ("'You'" 46). Yet "I'm not

really a writer," Campbell insists, "I'm not. I'm really acommunityworker" (53);

writing,forher,isatoolincommunityeducationandhealing. ThouW:tHaljbreedchanged

her life-"[it] was like a miracle forme" (46)-Campbelldoes not claim that it saved

her life. Writing enters into acomplex relationship to her multiple heritages, as she

explains in the interview:

I believe everybody's life is in cycles. In the first cycle of my life, it was the Metis-the mixed

blood. That's a race in itself. It's a distinct culture. That was the one, for me, that was

associated with grandmothers, grandfathers, parents and language. The second cycle was the

Indian. When I was going to pieces, when technically I should have been dead from an

overdose, it was the Indian part that saved me from going overthe edge. The other part of my

life-the writing part-I think it was only at that point that Istarted to see the part of me that

was European. That was the part I had hated so long. ("'You'" 47)

Later in the interview, Campbell discusses herwork with Native writers:

I've learnedalot from non-Native writers, but my true development has come from exploring

ways to work with my own language and culture. Working with Native writers has helped me

notto hate the English language so much so that at least I can work with it and understandmy

own language too. (52)

In rejecting the label of "writer," Campbell is rejecting individualism over responsibilitytocommunity:"Ifyou'reanartistandyou'renotahealer,thenyou'renot an

artist-not in my sense ofwhat art is. Artisthemostpowerful ... it'sthemainhealing

tool. The artist in the old communities was the most sacred person of all" (Book84).

In thisliW:tt, Campbell became interested in theatre as atool for community work,

and in the late 1970s, she began to explore the possibility of developing a play with

Paul Thompson, the artistic director of Theatre Passe Muraille, a Toronto-based

alternative theatre. Thompson introduced Campbell to Linda Griffiths, a white

improvisational actress, and the three worked together in developingJessica, the play

based on Campbell's life and theparts she left outofHalJbreed("'You'" 52). Jessicaw as

first performed in 1982, with Griffiths in the title role. Campbell insisted that in

subsequent performances, the role should go to a Native actor, and when it was

remounted in 1986, TantooCardinalplayedJessica.

The Class(room) as Borderland 119

1be&okoffessica:A 7beatricalTransformation(1989), by Griffiths and Campbell,

documents theprocess ofcross-cultural collaboration in the making ofJessica. Divided

into three sections, it presents an account in two parts of the difficulties in the

relationship between Griffiths and Campbell both in creatingthe play and in working

through unfinished business later, and it concludes with the text of the play. In

Canadian postcolonial criticism, 7heBook oDessica has been read as aclassicexample

of colonial appropriation, beginning with the fact that Griffiths assumed primary

authorship in constructing the book. Helen Hoy, for example, reads the text as

"textual appropriation," but also as "postcolonial deposition" and "textual resistance." She suggests that" The Book o/Jessica, in all its ambivalence, can be read as

modelling aspects ofthe white scholarlNative writer relationship" (24). Other critics

have also focused on this collaboration (Boardman, Chester and Dudoward, Egan,

Perreault), but almost no one has focused on the text of the play. I was intrigued by

aMetis student's presentation on the book in a women's literature course; rather

dismissive ofGriffiths' angst in dealingwith Campbell, she focused instead on the play

and on the healing ceremony through which]essicacomesto reclaim herselffrom her

traumatic history. Inthe powerful last scene, which the student read dramatically for

us,]essicametaphorically gives birth to herself as she voices her name {175}.

Collaboration in the borderlands between writers ofdifferent heritages is not an

easyprocess, as 7'heBookoDessicademonstrates, but what is common to the texts I have

discussed-the literacy narratives, incest narratives, trauma narratives, writings from

the borderlands, published and unpublished-is the underlying commitment to

writing as knowledge and as healing. In this sense, writing in the borderlands is an

imaginingof community.

Universityo/Alberta

Edmonton,Alberta

Notes

IIamindebtedtonumerousclassesandstudents,whocontinuallyamazemewiththeirwillingness

totakerisks. I wouldespecially liketothank TanyaCahoon,RomitaChoudhury, Margaret DeCorby,

andCatherineGutwin fortheirworkand its impetus to my resesarch and thinking in this paper. I would

also like tothankJerry Krepakevich andNasrin Rahimieh fortheirunstinting daily encouragement in

developing these ideas on teaching. And finally, grateful thanks to Lahoucine Ouzgane and Andrea

Lunsford for providing the opponunitytowritethrough ablock.

2My discussion ofthe contact zone owes much to Elizabeth Ellswonh'scritique ofthe ideological

assumptions underlying critical pedagogy inherarticle, "Why Doesn'tthisFeelEmpowering? Working

Through the Repressive Myths of Critical Pedagogy," and her response to critics, "The Question

Remains: How WillYouHoldAwarenessoftheLimitsofYour Knowledge?" AlthoughIdonot develop

this point in the paper, I would argue that there is a clear congruence between the goals and practices

of critical pedagogy and those of contact-zone teaching. Coming from afeminist and poststructuralist

perspective, Ellswonh begins her critique by asking, "What diversity do we silence in the name of

'liberatory' pedagogy?" (·Why" 91; ·Question" 399), and concludes with acallfor"a pedagogy ofthe

unknowable" ("Why" 110). My discussion oflimits in contact-zone pedagogical practice concerning

safe houses andthe teacher-student relationship is informed by Ellswonh'sanalysis of "the repressive

fictions of classroom dialogue" ("Why" 101) andthe principle of "knowability" underlyingthe position

of the critical educator ("Question" 400). Another point of connection between critical pedagogy and

contact-zone theorizing (which I don't explore) is the emphasis on (auto)ethnography. EI1swonh asks,

"What is critical pedagogy's relationship, when embedded within particular discourses and practices of

120JAC

ethnography, to the historical emergence and use of ethnography within colonialism and subsequent

deployment of ethnography in many other projects that see difference as Other?" ("Question" 399).

Although Ellsworth's work has been critical to my thinking, I have not gone on toconsiderthe

concept of borderland in the literature of critical pedagogy.

Works Cited

Allen, Paula Gunn. "'Border' Studies: The Intersection of Gender and Color." The EthnicCanon:

Histories,lnstitutions.andlnteruentions. Ed. DavidPalumbo-Liu. Minneapolis: U ofMinnesotaP,

1995. 31-47.

Anderson, Benedict. lmaginedCommunities:ReflectionsontheOriginandSpreadofNationalism. Rev.ed

London: Verso, 1991.

Anzaldua, Gloria. BorderlandslLaFrontera. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987.

Bloom, LynnZ. "Freshman Composition as aMiddle-Class Enterprise." CollegeEnglish 58.6 (1996):

654-75.

Boardman,KathleenA. "Autobiography as Collaboration: TheBookoffessica." TextualStudiesinCanada

4 (1994): 28-39.

Campbell, Maria. Halfbreed. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1973.

- . ·'YouHavetoOwn Yourself'." Interview with Doris Hillis. PrairieFire9.3 (1988):44-58.

Chester, Blanca, and Valerie Dudoward. "Journeys and Transformations." TextualStudies in Canada 1

(1991): 156-77.

Chow,Rey. WritingDiaspara:Tacticsoflnterventionin ConremporaryCulturalStudies. Bloomington: Indiana

UP,1993.

Danica, Elly. Don't:A Woman j Word. Charlottetown: Gynergy Books, 1988.

Egan, Susanna. "The Book ofJessica: The Healing Circle of a Woman's Autobiography." Canadian

Literature 144 (1995): 10-26.

Ellsworth, Elizabeth. "The Question Remains: How Will You HoldAwareness ofthe Limits of Your

Knowledge?" HarvaraEducationaiReview60 (1990): 396-404.

- . "Why Doesn't this Feel Empowering? Working Through the Rel'ressive Myths of Critical

Peda2ogy." HarvardEducatiOnalReview59 (1989):297-324. Rl't. inFermnismsandCriticalPedagogy.

Ed. Carmen Luke andJennifer Gore. New York: Routledge, 1992. 90-119.

Griffiths, Linda, andMariaCampbell. TheBookoffessica:A Theatrical Transformation. Toronto: Coach

HouseP, 1989.

Hamilton,SharonJean. My NamejnotSusie:A LifeTransformedby Literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/

Cook,1995.

Herman,JudithLewis. TraumaandRecavery. New York: BasicBooks-HarperCollins, 1992.

Hoy, Helen. "'When YouAdmit You'rea Thief, Then You Can beHonourable': NativelNon-Native

Collaboration in TheBookofJessica." Canadian Literature 136 (1993):24-39.

Lesser, Wendy, ed. HidinginPlainSight: £5saysin CriticismandAutobiograpby. San Francisco: Mercury

House, 1993.

McFarlane,AlexanderC., andBessel A. van der Kolk. "Traumaandlts Challenge to Society." Traumatic

Stress: TheEffectsofOverwhelmingExperienceonMind,BotlJ.andSociety. Ed. Bessel A. vander Kolk,

AlexanderC. McFarlane, and LarsWeisaeth. New York: GuilfordP, 1996.24-46,

Miller, Richard E. "Fault Lines in the Contact Zone." College English 56.4 (1994): 389-408.

The Class(room) as Borderland 121

Monture-OKanee, Patricia A. "Introduction-Survivinj the Contradictions: Personal Notes on

Academia." BreakingAnonymity: Tbe Chilly OimateJor Women Faculty. Ed The Chilly Collective.

Waterloo,ON: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 1995.11·28.

Morrison, Toni. BelO'lJed. 1987. New York: Plume, 1988.

Noble,Jean. "RedRunnin.,gShoes." LO'IJinginFear:AnAnthow~ojLesbianandGaySuroivorsofChildhood

Sexual Abuse. Ed. {,lueer Press Collective. Toronto: {,lueer P, 1991. 28·42.

Perreault,Jeanne. "Writing Whiteness:LindaGriffiths'sRacedSubjectivityin TbeBookofJessica." Essays

on Canadian Writing60 (1996): 14-31.

Plischke,Helen. "Bum Victim a 'Caring, GivingPerson'." EdmontonJoumal4 Dec. 1993: B1.

Pratt, Mary Louise. "Arts ofthe Contact Zone." Profession 91. New York: MLA, 1991. 33-40.

- . "Daring to Dream: Re-Visioning Culture and Citizenship." Critical Theory and the Teaching of

Literature:Politics, Curriculum,I-'edagogy. Ed.JamesF.SlevinandArt Young. Urbana:NCTE, 1996.

3·20.

- . "Linguistic Utopias." TbeLinguisticsoJWriting:ArgumentsbetweenLanguageandLiterature. Ed Nigel

Fabb,DerekAttridge,AlanDurant,andColinMacCabe. New YorK: Methuen, 1987.48-66.

Royster,JacquelineJones. "When the First Voice You Hear Is Not YourOwn." CollegeCompositionand

Communication47.1 {1996}:29-40.

Said, Edward W. "Introduction: Secular Criticism." The World, the Text, and the Critic. Cambridge:

Harvard UP, 1983.

- . "Opponents, Audiences, Constituencies, and Community." ThePoliticsofInterpretation. Ed W.J. T.

Mitchell. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1983. 7-32.

Sommer,Doris. "ResistingtheHeat: MenchU, Morrison, andIncompetentReaders." CulturesofUnited

States Imperialism. Ed. Amy Kaplan and Donald E. Pease. Durham: Duke UP, 1993. 407·32.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. "Can theSubaltemSpeak?" MarxismandtheInterpretationofCulture. Ed.

Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1988. 271·313.

- . "GayatriSpivakon the Politics ofthe Subaltern." Interview with Howard Winant. Socialist Review

20.3 (1990): 81·97.

Trinh,Minh·haT. Woman,Native,Other:WritingPostcokinialityandFeminism.Bloomingoon:JndianaUP,

1989.

van der Kolk, Bessel A., AlexanderC. McFarlane, andLars Weisaeth, eds. Traumatic Stress: The Effects

ofOverwhelmingExperienceon Mind, Body,andSociety.NewYork: GuilfordP, 1996.

Walker, Alice. "JnSearchofOurMothers'Gardens." In Search ofOurMothers'Garrkns. SanDiego:HBJ,

1984. 231-43.

Williams,Patricia. "Mirrors and Windows." TheAlchemy ofRaceandRights. Cambridge: Harvard UP,

1991. 166·78.

Williams, Raymond Keywords:A VocabularyofCultureandSociety. Glasgow: Fontana-Croom Helm,

1976.